Our generation

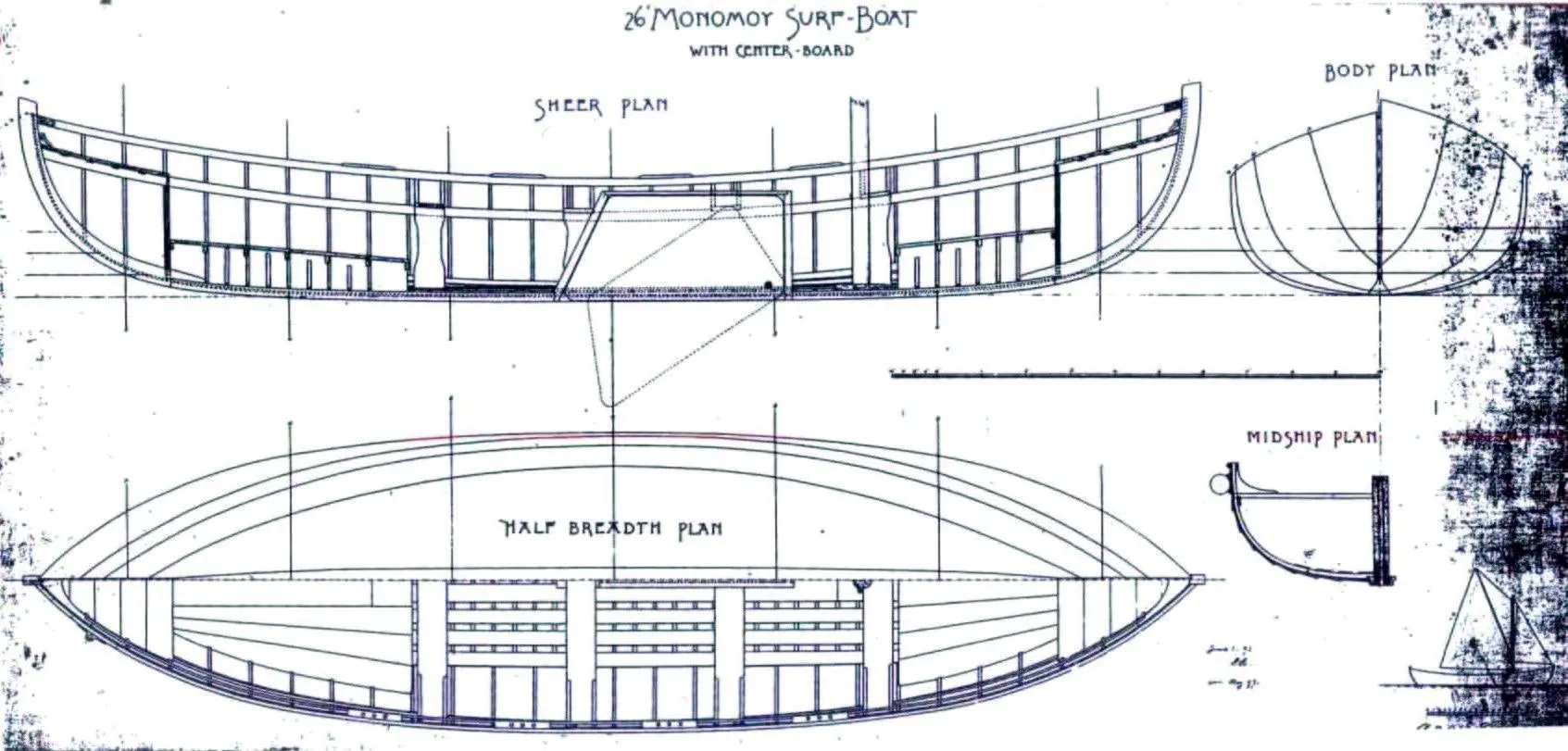

Whaleboat racing competition took its current form in the Bay Area in 1965 under the sponsorship of maritime companies, using U.S. Coast Guard “Monomoys” (also known as lifeboats or whaleboats) built in the 1930s and 40s. By 1982, the Bay Area Whaleboat Rowing Association was formed to provide standards for safety and competition as well as coordinate regattas and other activities. By the early 80s, new whaleboats were being built for the specific purpose of racing.

ERC was formed in 1980, and at that time, was a stepchild of the mainstream San Francisco rowing scene — it was the only “non-maritime” whaleboat rowing club in the area, lacking a sponsor in the form of a large shipping company, city port, or Coast Guard jocks. As the story goes, we inherited the nickname "Renegade Bastards" in 1985, during the notorious Alcatraz race. American President Lines’ Port Captain Carl Larkin was the race officiator (who was very prominent and one of the most influential people in whaleboat rowing at the time), and he was not pleased that ERC had won. After the awards ceremony he declared us “Renegade Bastards!!” and the name stuck. When we finally got our own boat in 1986, we named it the Renegade.